Palais Royal

The Palais-Royal (French pronunciation: [pa.lɛ ʁwa.jal]) is a former royal palace located in the 1st arrondissement of Paris, France. The screened entrance court faces the Place du Palais-Royal, opposite the Louvre. Originally called the Palais-Cardinal, it was built for Cardinal Richelieu from about 1633 to 1639 by the architect Jacques Lemercier. Richelieu bequeathed it to Louis XIII, and Louis XIV gave it to his younger brother, the Duke of Orléans. As the succeeding dukes of Orléans made such extensive alterations over the years, almost nothing remains of Lemercier’s original design.

The Palais-Royal now serves as the seat of the Ministry of Culture, the Conseil d’État and the Constitutional Council. The central Palais-Royal Garden (Jardin du Palais-Royal) serves as a public park, and the arcade houses shops.

History

Palais-Cardinal

Originally called the Palais-Cardinal, the palace was the personal residence of Cardinal Richelieu.[1] The architect Jacques Lemercier began his design in 1629;[2] construction commenced in 1633 and was completed in 1639.[1] The gardens were begun in 1629 by Jean Le Nôtre (father of André Le Nôtre), Simon Bouchard, and Pierre I Desgots, to a design created by Jacques Boyceau.[3] Upon Richelieu’s death in 1642 the palace became the property of the King and acquired the new name Palais-Royal.[1]

After Louis XIII died the following year, it became the home of the Queen Mother Anne of Austria and her young sons Louis XIV and Philippe, duc d’Anjou,[4] along with her advisor Cardinal Mazarin.

From 1649, the palace was the residence of the exiled Henrietta Maria and Henrietta Anne Stuart, wife and daughter of the deposed King Charles I of England. The two had escaped England in the midst of the English Civil War and were sheltered by Henrietta Maria’s nephew, King Louis XIV.

The Palais Brion, a separate section near the rue de Richelieu to the west of the Palais-Royal, was purchased by Louis XIV from the heirs of Cardinal Richelieu. Louis had it connected to the Palais-Royal. It was at the Palais Brion that Louis had his mistress Louise de La Vallière stay while his affair with Madame de Montespan was still an official secret.[5]

Philippe I, Duke of Orléans

Philippe de France, duc d’Orléans the younger brother of Louis XIV.

Henrietta Anne was married to Louis’ younger brother, Philippe de France, duc d’Orléans in the palace chapel on 31 March 1661. After their marriage, Louis XIV allowed his brother and wife to use the Palais-Royal as their main Paris residence. The following year the new duchess gave birth to a daughter, Marie Louise d’Orléans, inside the palace. She created the ornamental gardens of the palace, which were said to be among the most beautiful in Paris. Under the new ducal couple, the Palais-Royal would become the social center of the capital.

The palace was redecorated and new apartments were created for the Duchess’s maids and staff. Several of the women who later came to be favourites to King Louis XIV were from her household: Louise de La Vallière, who gave birth there to two sons of the king, in 1663 and 1665; Françoise-Athénaïs, marquise de Montespan, who supplanted Louise; and Angélique de Fontanges, who was in service to the second Duchess of Orléans.

The court gatherings at the Palais-Royal were famed all around the capital as well as all of France. It was at these parties that the crème de la crème of French society came to see and be seen. Guests included the main members of the royal family like the Queen Mother, Anne of Austria; the duchesse de Montpensier, the Princes de Condé and de Conti. Philippe’s favourites were also frequent visitors.

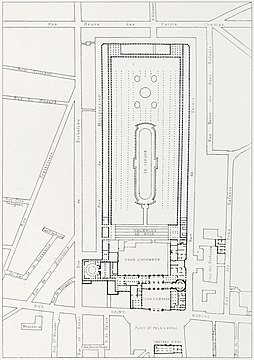

General site plan (1692) by François d’Orbay, showing the gardens as redesigned by André Lenôtre around 1674

After Henrietta Anne died in 1670 the Duke took a second wife, the Princess Palatine, who preferred to live in the Château de Saint-Cloud. Saint-Cloud thus became the main residence of her eldest son and the heir to the House of Orléans, Philippe Charles d’Orléans known as the duc de Chartres.[6]

The Palais Brion on the 1739 Turgot map of Paris

The Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture occupied the Palais Brion from 1661 to 1691 and shared it with the Académie Royale d’Architecture from 1672.[7] The royal collection of antiquities was installed there under the care of the art critic and official court historian André Félibien, who was appointed in 1673.

About 1674 the Duke of Orléans had André Lenôtre redesign the gardens of the Palais-Royal.[8]

After the dismissal of Madame de Montespan and the arrival of her successor, Madame de Maintenon, who forbade any lavish entertainment at Versailles, the Palais-Royal was again a social highlight.[9]

In 1692, on the occasion of the marriage of the duc de Chartres to Françoise Marie de Bourbon, Mademoiselle de Blois, a legitimised daughter of Louis XIV and Madame de Montespan, the King deeded the Palais-Royal to his brother. The new couple did not occupy the northeast wing, where Anne of Austria had originally lived, but instead chose to reside in the Palais Brion. For the convenience of the bride, new apartments were built and furnished in the wing facing east on the rue de Richelieu.[6]

It was at this time that Philippe commissioned a Grande Galerie along the rue de Richelieu for his famous Orleans Collection of paintings, which was easily accessible to the public. Designed by the architect Jules Hardouin-Mansart,[10] it was constructed around 1698–1700 and painted with Virgilian subjects by Coypel. The cost of this reconstruction totaled about 400,000 livres.[11] Hardouin-Mansart’s assistant, François d’Orbay, prepared a general site plan, showing the Palais-Royal before these alterations were made.

Philippe II, Duke of Orléans

When the Duke of Orléans died in 1701, his son became the head of the House of Orléans. The new Duke and Duchess of Orléans took up residence at the Palais-Royal. Two of their daughters, Charlotte Aglaé d’Orléans, later the Duchess of Modena, and Louise Diane d’Orléans, later the Princess of Conti, were born there.

The duc d’Orléans’ Council in 1716, with Cardinal Fleury sitting at the Palais-Royal. Gobelins tapestry overdoors are woven with the Orléans arms.

At the death of Louis XIV in 1715, his five-year-old great-grandson succeeded him. The Duke of Orléans became Regent for the young Louis XV, setting up the country’s government at the Palais-Royal, while the young king lived at the nearby Tuileries Palace. The Palais-Royal housed the magnificent Orléans art collection of some 500 paintings, which was arranged for public viewing until it was sold abroad in 1791.

He commissioned Gilles-Marie Oppenord to redesign the apartments of the Duchess on the ground floor in 1716 and to decorate the Grand Appartement of the Palais Brion in the light and lively style Régence that foreshadowed the Rococo, as well as the Regent’s more intimate petits appartements. Oppenord also made changes to the Grande Galerie of the Palais Brion and created a distinctive Salon d’Angle, which connected the Grand Appartement to the Grande Galerie along the rue de Richelieu (1719–20; visible on the 1739 Turgot map of Paris). All of this work was lost, when the Palais Brion was demolished in 1784 for the installation of the Théâtre-Français, now the Comédie-Française.[12][13]

Louis d’Orléans

Palais-Royal on the 1739 Turgot map of Paris with the gardens as redesigned by Claude Desgots in 1729. The palace itself fronts on its small square.

After the Regency, the social life of the palace became much more subdued. Louis XV moved the court back to Versailles and Paris was again ignored. The same happened with the Palais-Royal. Louis d’Orléans succeeded his father as the new Duke of Orléans in 1723. He and his son Louis Philippe lived at the other family residence in Saint-Cloud, which had been empty since the death of the Princess Palatine in 1722.

Claude Desgots redesigned the gardens of the Palais-Royal in 1729.[14]

Louis Philippe I

In 1752 Louis Philippe I succeeded his father as the Duke of Orléans. The Palais-Royal was soon the scene of the notorious debaucheries of Louise Henriette de Bourbon who had married to Louis Philippe in 1743. New apartments (located in what is now the northern section of the Rue-de-Valois wing) were added for her in the early 1750s by the architect Pierre Contant d’Ivry.[15] She died at the age of thirty-two in 1759. She was the mother of Louis Philippe II d’Orléans, later known as Philippe Égalité. A few years after the death of Louise Henriette, her husband secretly married his mistress, the witty marquise de Montesson, and the couple lived at the Château de Sainte-Assise where he died in 1785. Just before his death, he completed the sale of the Château de Saint-Cloud to Queen Marie Antoinette.

Louis Philippe II

Louis Philippe II d’Orléans was born at Saint-Cloud and later moved to the Palais-Royal and lived there with his wife, the wealthy Louise Marie Adélaïde de Bourbon whom he had married in 1769. The duke controlled the Palais-Royal from 1780 onward. The couple’s eldest son, Louis-Philippe III d’Orléans, was born there in 1773. Louis Philippe II succeeded his father as the head of the House of Orléans in 1785.

Theatres of the Palais-Royal

Plan of the Palais-Royal with the theatre in the east wing (Blondel, Architecture françoise, 1754)

The Palais-Royal had contained one of the most important public theatres in Paris, in the east wing on the rue Saint-Honoré (on a site just to the west of what is now the rue de Valois).[16] It was built from 1637 to 1641 to designs by Lemercier and was initially known as the Great Hall of the Palais-Cardinal. This theatre was later used by the troupe of Molière beginning in 1660, by which time it had become known as the Théâtre du Palais-Royal. After Molière’s death in 1673 the theatre was taken over by Jean-Baptiste Lully, who used it for his Académie Royale de Musique (the official name of the Paris Opera at that time).[17]

1780 plan of the Palais-Royal with Moreau’s opera house (1770–1781)

The Opera’s theatre was destroyed by fire in 1763, but was rebuilt to the designs of architect Pierre-Louis Moreau Desproux on a site slightly further to the east (where the rue de Valois is located today) and reopened in 1770. This second theatre continued to be used by the Opera until 1781, when it was also destroyed by fire, but this time it was not rebuilt. Moreau Desproux also designed the adjacent surviving entrance facades of the Palais-Royal.[18]

At the request of Louis Philippe II two new theatres were constructed in the Palais-Royal complex shortly after the fire. Both of these new theatres were designed by Victor Louis, the architect who also designed the shopping galleries facing the garden (see below). The first theatre, which opened on 23 October 1784, was a small puppet theatre in the northwest corner of the gardens at the intersection of the Galerie de Montpensier and the Galerie de Beaujolais.[19] Initially it was known as the Théâtre des Beaujolais, then as the Théâtre Montansier, after which Victor Louis enlarged it for the performance of plays and operas. Later, beginning with the political turmoil of the Revolution, this theatre was known by a variety of other names. It was converted to a café with shows in 1812, but reopened as a theatre in 1831, when it acquired the name Théâtre du Palais-Royal, by which it is still known today.[20]

The Salle Richelieu, designed and constructed 1786–1790 by Victor Louis, became the theatre of the Comédie-Française in 1799.

Palais-Royal (c. 1790) with Victor Louis’ second theatre on the left and the rue de Valois replacing Moreau’s opera on the right

Louis Philippe II’s second theatre was larger and located near the southwest corner of the complex, on the rue de Richelieu. He originally intended it for the Opera, but that company refused to move into it. Instead he offered it to the Théâtre des Variétés-Amusantes, formerly on the boulevard du Temple but since 1 January 1785 playing in a temporary theatre in the gardens of the Palais-Royal. This company changed its name to Théâtre du Palais-Royal on 15 December 1789, and later moved into the new theatre upon its completion, where they opened on 15 May 1790. On 25 April 1791 the anti-royalist faction of the Comédie-Française, led by Talma, left that company’s theatre on the left bank (at that time known as the Théâtre de la Nation, but today as the Odéon), and joined the company on the rue de Richelieu, which promptly changed its name to Théâtre Français de la rue de Richelieu. With the founding of the French Republic in September 1792 the theatre’s name was changed again, to Théâtre de la République. In 1799 the players of the split company reunited at the Palais-Royal, and the theatre officially became the Comédie-Française, also commonly known as the Théâtre-Français, names which it retains to this day.[21]

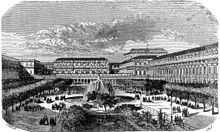

Shopping arcades

Louis Philippe II also had Victor Louis build six-story apartment buildings with ground-floor colonnades facing the three sides of the palace garden between 1781 and 1784. On the outside of these wings three new streets were constructed in front of the houses that had formerly overlooked the garden: the rue de Montpensier on the west, rue de Beaujolais to the north, and rue de Valois on the east.[22] He commercialised the new complex by letting out the area under the colonnades to retailers and service-providers and in 1784 the shopping and entertainment complex opened to the public. Over a decade or so, sections of the Palais were transformed into shopping arcades that became the centre of 18th-century Parisian economic and social life.[23]

Though the main part of the palace (corps de logis) remained the private Orléans seat, the arcades surrounding its public gardens had 145 boutiques, cafés, salons, hair salons, bookshops, museums, and countless refreshment kiosks. These retail outlets sold luxury goods such as fine jewelry, furs, paintings and furniture to the wealthy elite. Stores were fitted with long glass windows which allowed the emerging middle-classes to window shop and indulge in fantasies. Thus, the Palais-Royal became one of the first of the new style of shopping arcades and became a popular venue for the wealthy to congregate, socialise and enjoy their leisure time. The redesigned palace complex became one of the most important marketplaces in Paris. It was frequented by the aristocracy, the middle classes, and the lower orders. It had a reputation as being a site of sophisticated conversation (revolving around the salons, cafés, and bookshops), shameless debauchery (it was a favorite haunt of local prostitutes), as well as a hotbed of Freemasonic activity.[24]

Designed to attract the genteel middle class, the Palais-Royal sold luxury goods at relatively high prices. However, prices were never a deterrent, as these new arcades came to be the place to shop and to be seen. Arcades offered shoppers the promise of an enclosed space away from the chaos that characterised the noisy, dirty streets; a warm, dry space away from the elements; and a safe-haven where people could socialise and spend their leisure time. Promenading in the arcades became a popular eighteenth century pastime for the emerging middle classes.[25]

From the 1780s to 1837, the palace was once again the centre of Parisian political and social intrigue and the site of the most popular cafés. The historic restaurant “Le Grand Véfour“, which opened in 1784, is still there. In 1786, a noon cannon was set up by a philosophical amateur, set on the prime meridian of Paris, in which the sun’s noon rays, passing through a lens, lit the cannon’s fuse. The noon cannon is still fired at the Palais-Royal, though most of the ladies for sale have disappeared, those who inspired the Abbé Delille‘s lines:

Dans ce jardin on ne rencontre

Ni prés, ni bois, ni fruits, ni fleurs.

Et si l’on y dérègle ses mœurs,

Au moins on y règle sa montre.[26]

(“In this garden one encounters neither meadows, nor woods, nor fruits, nor flowers. And, if one upsets one’s morality, at least one may reset one’s watch.”)

The Cirque du Palais-Royal, constructed in the center of the garden, has been described as “a huge half-subterranean spectacle space of food, entertainments, boutiques, and gaming that ran the length of the park and was the talk of the capital.”[27] It was destroyed by fire on 15 December 1798.[28]

Inspired by the souks of Arabia, the Galerie de Bois, a series of wooden shops linking the ends of the Palais Royal and enclosing the south end of the garden, was first opened in 1786.[29] For Parisians, who lived in the virtual absence of pavements, the streets were dangerous and dirty; the arcade was a welcome addition to the streetscape as it afforded a safe place where Parisians could window shop and socialise. Thus, the Palais-Royal began what architectural historian Bertrand Lemoine describes as “l’Ère des passages couverts” (the Arcade Era), which transformed European shopping habits between 1786 and 1935.[30]

Palais de l’Égalité and the Revolution

Galeries de bois at the Palais-Royal, by Theodor Josef Hubert Hoffbauer, lithograph, c. 1825

During the revolutionary period, Philippe d’Orléans became known as Philippe Égalité and ruled at the Palais de l’Égalité, as it was known during the more radical phase of the Revolution.[31] He had made himself popular in Paris when he opened the gardens of the palace to all Parisians. In one of the shops around the garden Charlotte Corday bought the knife she used to stab Jean-Paul Marat. Along the galeries, ladies of the night lingered, and smart gambling casinos were lodged in second-floor quarters.

The Marquis de Sade referred to the grounds in front of the palace in his Philosophy in the Bedroom (1795) as a place where progressive pamphlets were sold.

Upon the death of the Duke, the palace’s ownership lapsed to the state, whence it was called Palais du Tribunat.[31] The Comédie-Française, the state theatre company, was reorganised by Napoleon in the décret de Moscou on 15 October 1812, which contains 87 articles.[32]

Bourbon restoration to Second Empire

After the Restoration of the Bourbons, at the Palais-Royal the young Alexandre Dumas obtained employment in the office of the powerful duc d’Orléans, who regained control of the Palace during the Restoration.

The duke had Pierre-François-Léonard Fontaine draw up plans to complete work left unfinished by the duke’s father. Fontaine’s most significant work included the western wing of the Cour d’Honneur, the Aile Montpensier, and with Charles Percier, what was probably the most famous of Paris’s covered arcades, the Galerie d’Orléans, enclosing the Cour d’Honneur on its north side. Both were completed in 1830. The Galerie d’Orléans was demolished in the 1930s, but its flanking rows of columns still stand between the Cour d’Honneur and the Palais-Royal Garden.[33]

In the Revolution of 1848, a Paris mob attacked and looted the royal residence Palais-Royal, particularly the art collection of King Louis-Philippe. During the Second French Republic, the Palais was briefly renamed the “Palais-National”.[34]

During the Second French Empire of Napoleon III, the Palais-Royal became home to the cadet branch of the Bonaparte family, represented by Prince Napoleon, Napoleon III’s cousin. A lavish dining room was constructed in the Second Empire style, and is now known as the Salle Napoleon of the Council of State.[35]

During the final days of Paris Commune, on May 24 1871, the Palais, seen as a symbol of aristocracy, was set afire by the Communards, but suffered less damage than other government buildings. As a result, it became the temporary (and later permanent) home of several state institutions, including the Conseil d’Etat, or State Council.[36]

The Palais-Royal today

Today, the Palais-Royal is the home of the Conseil d’État, the Constitutional Council, and the Ministry of Culture.

South Facade

The buildings of the Palais-Royal face south to the Place du Palais-Royal and the Louvre across the Rue de Rivoli. The central part of the Palace is occupied by the Conseil-d’État, or State Council. It has three floors, and is topped by a low cupola and a rounded pediment filled with sculpture. Two arched passages under the central building lead to the Courtyard of Honor behind. In the east wing, to the right, are offices of the Ministry of Culture and Communication. The two wings of the building have triangular fronts filled with sculpture, inspired by classical architecture and typical of the Louis XIV style.[37]

-

Sculpture of the south front, by Augustin Pajou

On the west side of the Council building is Place Colette, and the Salle Richelieu of the Comédie Française. Behind that are the offices of the Constitutional Council. On the left side of the Salle Richelieu is another small square, Place André Malraux.[38]

Council of State

-

Dome over the Stairway of Honor with gilded bursting pomegranate emblems of Philippe d’Orléans

The Council of State, created by Napoleon in 1799, inherited many of the functions of the earlier Royal Council, acting both as a consultant to the government and a kind of Supreme Court. It was installed in the Palais-Royal in 1875.[39]

The Conseil has its own courtyard, facing out onto the Place du Palais-Royal and the Rue du Rivoli. Inside is the grand horseshoe stairway of honor, which curves upward along the walls to the landing on the first floor. It is decorated with theatrical effects, including ionic columns, and blind arches giving the illusion of bays. A trompe-l’oeil painting in an archway appears to give a view of a classical statue, above which putti hold wreathes around a bust of Cardinal Richelieu. The stairway was made by Pierre Contant d’Ivry in 1765.[40]

The most lavish room of the Council is the Hall of the Tribunal of Conflicts, a kind of courtroom installed in the former dining room of Duchess of Orleans, built by the architect Contant d’Ivry in 1753.[41] It still preserves much of its original decoration, with pilasters and columns, and decorative medallions of putti representing the four seasons and the four elements. The ceiling has a trompe l’oeil painting from 1852 depicting a balustrade and a view of the sky.[42]

The General Assembly chamber was first a chapel, then, under Price Napoleon, a gallery of paintings. It has been changed more than any of the other rooms in the Council. At one end is a long table, with a seat in the center for the Vice President of the Assembly, who chairs the meetings, and the six presidents of the sections of Council. The decoration of the room is particularly rich and varied, with medallions and cameos and allegorical paintings illustrating the various codes of law and the administrative departments. Below these are four more recent large murals, installed between 1916 and 1926, on the theme of France at Work. They depict agriculture (workers in the fields), commerce (the Port of Marseilles), urban labor (Paris workers maintaining the Plae de la Concorde), and intellectual labor.[43]